“Between skin and skin there is only light.”

John Fowles, The Magus

The goddess Sarasvati once personified the river Sarasvati, but today she is revered as the deity of arts and music, knowledge and learning. Her forgotten original meaning is linked to the fact that the river dried up long ago – according to some sources about 4,000 years ago – allegedly due to sudden climate change and virtually disappeared, but in the wake of her earliest mention in the Ṛgveda, she acquired a mythological status. Even as her stature as a river goddess declined, Sarasvati survived in various forms as a perennial source of inspiration, containing within herself the memory of a different past in which women and water, as sources of life and conditions for survival, were inextricably linked. This is why the bodies of goddesses in ancient clay depictions often take the form of jugs, vases or water vessels (see Gimbutas 1982).

Neolithic Venus figurine called “Red-haired goddess” from Bačka region, northern Serbia.

None of this was on my mind when I started thinking about the research question that would direct my thoughts as I walked along the 14 km long Rižana River, from its source to its mouth in the Adriatic Sea. The walking seminar methodology was completely new to me and I was distinctly unsure about it — even confused.

But I liked it instinctively. Much like the quote from John Fowles’ magnum opus, The Magus, cited above, it felt mysterious yet forceful. This quote struck me as being closely related to a day-long hike in the middle of summer. However, even now, as I write this, I am not sure if it has anything to do with it. Quite possibly not. But still, what is this in-between?

Is it the space between the dichotomised ‘object’ and ‘subject’ of study? Is it the gap between what we are trying to understand and the understanding itself? Linking the experience of walking with the experience of thinking directly, as in the walking seminar, suddenly seemed a promising way to shed light on this stubborn problem that continues to plague Western thought paradigms more generally. It certainly made me realise the extent to which one can be physically involved in the process of thinking: you move, breathe, get hot and feel tired while actively observing the phenomenon under study (first in yourself, then in a group). It is also an attractive alternative to sitting at a computer. Since researchers are entirely reliant on their own prior knowledge and field of reference, which they cannot verify or ‘objectify’ during the research itself, experience and associative thinking become the central driving forces of this method – a method that is dynamic and unbounded in its very essence.

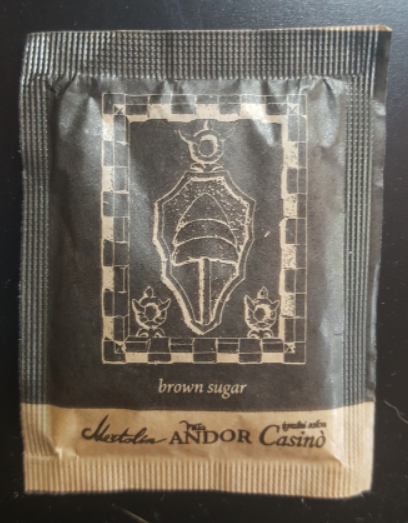

It was only at breakfast the next morning that I was struck by a research question when I saw Villa Andor’s business card at the reception desk and later found the same image on a sugar sachet.

Sugar sachet with the unusual emblem of Villa Andor.

We had spent the night there. The card featured an unusual emblem that could be a jug or the body of a goddess (its curves were reminiscent of the famous Venus of Willendorf), with an image of a tree in the middle and horns on its head.

The Egyptian goddess Isis (mark the horns on her head).

As I was studying a course on female deities and early Tantra at the time, the tree (perhaps the Tree of Life?) and ‘the horns’ reminded me of attributes closely associated with depictions of ancient goddesses. These goddesses were protectors of animals and were often depicted (as on the Harappa seals, for example) as living in or growing out of trees. When the reception staff were unable to tell me anything specific about the meaning of their emblem or its origin, I found myself wondering what had been here 8,000 years ago, during the Neolithic period. For this period, the controversial archaeologist Maria Gimbutas put forward the idea of a matrilineal and matristic society, which she called ‘Old Europe’, in contrast to the later day patriarchy. Could there also have been numerous sites containing Venus figurines here, testifying to a social order in which the female principle ‘ruled’? There, feminine values were expressed through respect and care for all life forms, the worship of nature and natural processes, and equal relations between the sexes based on mutual cooperation rather than hierarchy. When Nataša mentioned the archaeological site of Sermin, where nails from the Roman period were found, among a multitude of facts and interesting tidbits about the Rižana River, my heart missed a beat. The old church of St Mary at the source of the Rižana River only further confirmed the relevance of asking questions about the river – today captured, confined and literally concreted over in places – through the prism of gender.

It was all the more fitting, then, that our hike, which was supposed to last a few hours, began with a walk through the labyrinth (which I couldn’t complete due to the heat) and ended in the evening after several unexpected stops and detours. I experienced this as a research method that is not – and should not be – linear and straightforward, but open, winding, in every way more like an intricate net. Above all, it is a method that encourages associative thinking, in which the initial question is merely a spark that can ignite many other legitimate questions and reflections.

Bits of information and some basic facts about the river, together with my observations and experiences (it is significant that this took place with a group of five women who were in no hurry and open to shaping the day spontaneously), began to organise my thoughts. The Rižana River actually aroused feelings of disappointment in all of us. Urša described it as ‘characterless’ because it had already been ‘decapitated’, so to speak, at its source due to the collection of drinking water and the prohibition of access. Nataša (R.) said that, given the visible devastation and degradation of the environment, she was beginning to understand how this river could turn you into an activist. After walking several kilometres on the scorching asphalt, I wondered where the river actually was. Standing by the sign on the lagoon section, I silently marvelled at how perverse it is that, even today, the Rižana is still the subject of violence, albeit discursive this time – whether in the form of discourses of Slovenianness or environmentalism – and is still a battleground for various interest groups. As our wine-tasting host, Eva Bordon, put it: “They cut us up like mortadella.”

I was reminded of Marija Sreš’s stories about the Sabarkantha women and indigenous people in northern Gujarat in India, whose forests were destroyed, forcing the men to work in cities as cheap labour. Women bore the greatest burden of supporting their families, and their lives were often accompanied by blows of disappointment from their husbands. Marija concludes that violence against nature is always linked to violence against women. This seemed an overly simplistic and exaggerated statement to me at first, but by the time we reached the end of our walking seminar alongside the Rižana River, I began to see it differently. This river was once of exceptional size and importance, as evidenced by the maps Urša showed us. Today, it still supplies most of the region with drinking water, even though it is practically invisible, having mostly degraded into a stream and, in some places, an inconspicuous trickle squeezed between the highway and the railroad tracks. The river’s mouth at the so-called ‘shellfish cemetery’ seemed a fitting metaphorical end for a river that is still being exploited in several ways yet remains invincible. Saying that it is like a woman seems unnecessary and exaggerated! And yet …

A walking seminar along the Rižana River was held in July 2020, attended by five female participants — Ana Jelnikar, Nataša Rogelja Caf, Nataša Gregorič Bon, Maja Petrović Šteger, and Urša Kanjir. The event took place within the framework of the project Experiencing Water Environments and Environmental Changes: An Anthropological Study of Water in Albania, Serbia, and Slovenia (funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency, J6-1803).

Published October 2025. 2025/23

https://doi.org/10.3986/30240662_23

REFERENCES

Gimbutas, M. (1982). The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe, 6500-3500 BC, Myths and Cult Images, California: University of California.