As a child, I saw my grandmother cry a few times when she remembered her late brother Marcel. In 1944, as a Slovenian partisan, he fell under the Nazi fire at a quarry above Trieste. As a child, I did not understand why my grandmother was crying over an event that had happened more than forty years earlier. The only image I had of Marcel was a black-and-white photograph that hung in my grandmother’s house, and his photograph on the tombstone in the village cemetery. At her request, we grandchildren went to the cemetery every day in summer to water the flowers on his grave. Well, not just flowers. Clover, especially. It needs lots and lots of water.

The San Sabba Rice Mill in Trieste, Italy. The museum has the status of a national monument. The San Sabba Rice Mill was the only Nazi camp in Italy with a crematorium. It operated as an extermination concentration camp from 1944 until the end of the war in 1945.

I have visited the museum three times. The first time was many years ago as part of an excursion. The second time was in the summer of 2022, when I went alone. I examined all the exhibits in detail, read all the documents, and listened to and viewed all the stories presented on the ground floor of the museum. I also read the farewell letter entitled ‘Dear Mama!’, written by a Slovenian prisoner to his family on 5 April 1945, shortly before he was shot. This was just one of the many pieces of information there.

That same summer, my uncle told me the story of how my grandmother had been imprisoned for some time in Trieste during the Second World War. She was held in the infamous Via Coroneo prison, which was run by the Fascists before the Italian capitulation in September 1943 and then taken over by the Nazis. This was because my grandfather had escaped from the German soldiers and gone into hiding. My uncle did not see his mother (my grandmother) for ‘quite a long time’. A few weeks? A few months? Then, one day, a relative hitched up a cart, put my uncle on it, and they drove out of the village towards Trieste. To grandma. They received news that she had been released from prison and was coming home on foot. My uncle only remembers getting down from the cart and dancing in the road, overjoyed to see his mother again at last. He was four years old.

The village of Plavje, which is located just a stone’s throw from the Italian border in Slovenia today, belonged to Yugoslavia after the abolition of the Free Territory of Trieste in 1955. Previously, it had been part of the northern Zone A, which was under Anglo-American military administration, as opposed to the southern Zone B, which was under the military administration of the Yugoslav army. A small border correction. In favour of Yugoslavia.

On 8 May 2024, I visited the San Sabba Rice Mill for the third time as part of a walking seminar. I squatted in a corner, against two looming concrete walls. New infrastructure. Monumental infrastructure. Brutalism. Rough concrete. The architect has designed the monument so that it truly embodies a monumental character. You feel really small and insignificant standing next to this massive concrete structure. But even the way out of the camp, when it was still in operation, led, as a rule, into the open air. Through the crematorium furnace chimney.

The crematorium no longer exists. In the last days of the war, the executioners blew it up to cover up the evidence. Today, its location is marked by lines arranged in the shape of a staircase. The only original infrastructure still present in the museum are the death cells. Seventeen cells with open wooden doors and rounded edges. Cella della Morte. In each cell, a large number of people were crammed in. The room containing the death cells still has the original floorboards. They are not flat. The grout is uneven and the stone is sometimes chipped and broken. But it gives a touch of the original infrastructure of death.

Which research method should I use to explore the monument? The extreme slow walk exercise. During this walk, I explore the area behind the main building, which I missed on my first two visits. This is another monumental space surrounded by high concrete walls. This courtyard is dedicated to memorials erected by various organisations from different countries to commemorate the victims of the death camps. I stop in front of the memorial plaque erected by the Republic of Slovenia in October 2010. Attached to it is a copy of a farewell letter written by a Slovenian prisoner to his family on 5 April 1945, entitled “Dear Mama!”, before he was shot.

Dear Mother!

5. 4. 1945

I am writing to you to say

I will be shot today.

So goodbye forever.

Dear Mother goodbye

Dear Sister goodbye

Dear Father goodbye

Death to Fascism – Freedom to the People!

… Zorko

Draga Mama!

5. 4. 1945

Sporočam ti da jest sem

danes poklican za me ustreliti.

Torej zbogom za vekomaj.

Draga Mama zbogom

Draga Sestra zbogom

Dragi Tata zbogom

Smrt Fašizmu – Svoboda Narodu!

… Zorko

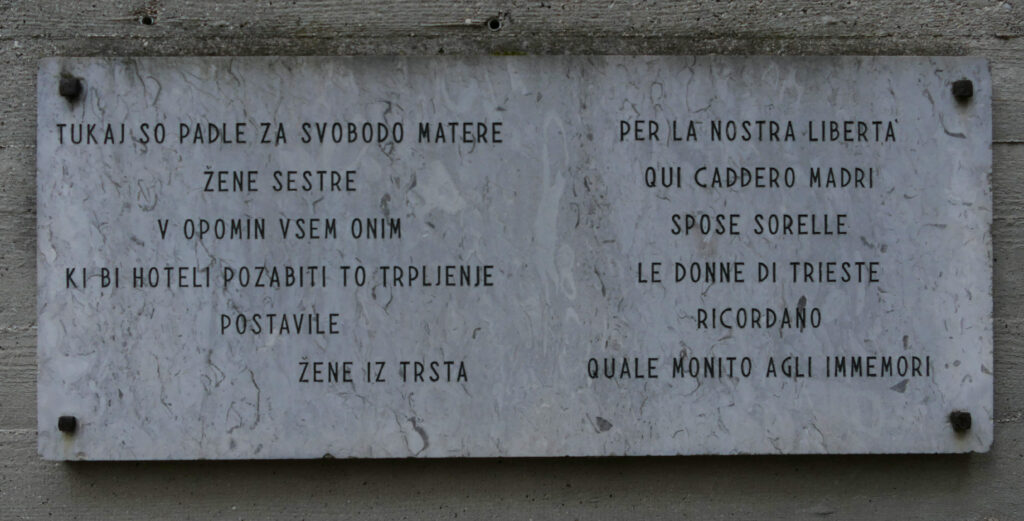

There is a second memorial plaque next to it:

Here mothers,

wives, sisters

have fallen for freedom in memory

of all those who want to forget this suffering.

Erected by

the wives of Trieste

The spelling and little grammatical irregularities of the Slovene language remind me of my grandma. She spent her childhood and youth in the period before the Second World War, when what is now western Slovenia was part of the Kingdom of Italy. The Italian fascist authorities closed Slovenian schools and banned the Slovenian language, so my grandma only learnt to write in Italian. This was a prelude to the Italianisation process, national oppression and the Second World War.

“The fourth article of The implementation of the Gentile Reform in South Tyrol and its effects on the educational biographies begins with an unequivocal explanation of the foundation of instruction, the teaching language: “In tutte le scuole elementari del Regno l’insegnamento è impartito nella lingua dello Stato” (In all elementary schools of the Reign, instruction must be held in the national language)” (Augschöll Blasbichler 2023). When, as a child, I asked my mother why my grandma had such “childish” handwriting, my mother told me that my grandma had only learned to write in Slovene after the Second World War.

Then I look again at this farewell letter. And it hits me. Tears come to my eyes. I cry. My grandma had been released from the prison on Via Coroneo. If she hadn’t, her next stop would probably have been the San Sabba Rice Mill. If she had gone there, I would not be here today. I would not be squatting in a corner under high concrete walls or slowly walking through a museum. My mother was born on 8 February 1946. Nine months after the day of victory over Nazi fascism.

Published Sept 2025. 2025/18