THE TEXTURES OF JOURNEYING

“Mud, clay, water, contour lines, Neolithic, nymphs,” I write on the first page of my notebook, which I name “Journ(al)eying”/Hodopisnik. I walk and write… My steps are flatter and more cautious than usual due to the muddy path leading through the woods from Plavje towards Podgorje (small villages in Slovenian Istria, located on the border between Slovenia and Italy, that were part of our Walking Seminar itinerary). I walk, immersed in the scent of early spring, which flourishes in various shades of green. Yielding to the rhythm of walking, to the sounds and scents that accompany me, I try to embrace the experience of walking itself. “How is walking shaping my way of being in this landscape?” I wonder. I reflect on the path beneath my feet and question the extent to which this path—whether shallow or hollow—, together with the rhythm of my walking, shapes my sensory experiences of being-on-the-way. I also wonder to what extent my perceptions and understandings of the path are conditioned by the guidance along the hollow ways of the Karst Edge by the archaeologist Dimitrij Mlekuž Vrhovnik. What guides the experience of walking, and to what extent is this experience already permeated with preconceived knowledge about the landscape? How – in what manner – does all this reveal itself through and within the hollow ways and their deep, sunken times?

Indeed, all this and more shapes both my subjective experiences and epistemological understandings, which, in this essay, seek to address the core question posed by the Walking Seminar along the Karst Edge (Kraški rob): How do invisible layers of landscape, pathways, and time reveal themselves through walking or movement? How do archaeological traces and trodden paths shape perceptions and navigate movement through the contemporary landscape?

After the first hour of walking from Plavje towards Podgorje, the sense of walking as a way of being gradually inhabits me. In the phenomenological sense, the way of walking becomes my current state of being-in-the-world or being-on-the-way, which conjoins both movement and pause. In fact, while walking, movement feels more innate or “natural” than its often mentioned corollary of pause or stasis, which is inherent to movement. The way of my thoughts is also part of this continuous movement, even though their rhythm and direction often differ from my steps and the actual physical movement. Following the rhythm of my steps, I try to forget the itinerary set before the Walking Seminar. I also try to set aside the maps (either analogue or digital) that we were given at the beginning of our hike along the archaeological routes or so-called hollow pathways. I try to forget time and the lively chatter of my colleagues (co-walkers)—everything that preconditions and determines my step and the way of my walking-thinking-writing. Only in this way can I focus on the very experience, the deep sediments and sunken sentiments of the time-space of my journ(al)eying (or walking-as-journeying).

PATHS – LINES – SEDIMENTS

Is it possible to journey without any baggage of knowledge or memory? What, in fact, is a path, and how is it made or remade? Who or what defines and creates it? Throughout history and today, path-making has been shaped by various geophysical processes and both non-human and human activities and interventions in specific times and places. All these processes, whether continuous or discontinuous, have reshaped routes, just as routes have reshaped the human way of moving and dwelling.

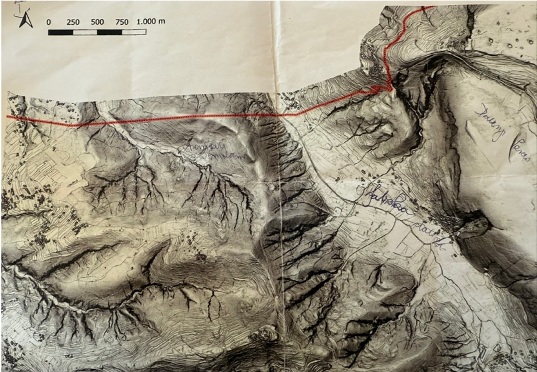

I reflect on the work of the anthropologist Tim Ingold, who, in his book Lines, emphasises that more important than routes or paths as lines is the meshwork generated through, by, or with these lines. This experience may be embraced both linearly (through the act of walking) and laterally (from a perspective “above”). On our walk along the Karst Edge, the lateral view was partly provided by geographical maps, which we received at the beginning of our journey to inform us about the geographical boundaries (the boundary between flysch and karst) and political borders (the border between Slovenia and Italy).

On the left side of the map above, contour lines are particularly prominent, creating an impression of dense, curved lines that map the flysch terrain. During our walk through this area, these dense lines were experienced through my flat and careful steps on the slippery texture of thick mud mixed with clay, which covered the sharp-edged stony line. The slippery terrain transposed me in my thoughts to the coast in the Basque Country, where I had been hiking some months earlier, marvelling at the coastal landscape, where the wind, the sea, and the geomorphological structure itself, like the boldest sculptors, have shaped the terrain, with is landscape and pathways as a way of dwelling.

On this journey along the forest path leading from Plavje to Podgorje, I listen to the archaeologist Dimitrij, who points out an overgrown area and shares stories about nymphs who, in Roman times, left their mark there. My archaeologically untrained eye searches for the spot where these nymphs sank. Feeling uneasy due to my lack of archaeological knowledge, I immediately comfort myself with the archaeologist’s remark that, to imagine an era, we need a good deal of imagination to envision the water that once found its way through the terrain and created the nymphs’ place of dwelling. Observing the site, I try to recall a time that now seems invisible, or perhaps only sunken deep within the layers of earth.

What is it that actually defines the path itself and my journey along it? The latter is shaped not so much by the path as a mere line winding across the terrain, but by the meshwork—using Tim Ingold’s concept—of sensory and mnemonic experiences, as well as geographically, archaeologically, and anthropologically conditioned knowledge, which together shape my being-on-the-way and journ(al)eying.

LINES-BORDERS-FENCES

Again, I pose the question of how the hollow-pathways are revealed through walking and/or journeying. In searching for an answer, I reflect on affective geographies, as defined by Yael Navaro-Yashin in The Make-Believe Space. In certain landscapes, where deep time is embedded both in the earth’s sediments and in people’s sentiments, it can, under specific contingencies, awaken and shift the hollow-pathways into shallow ones, traversing deep time through to the present. While walking, it seems that all these realms—hollow and shallow, deep and present—are often distinguished as if fixed and bounded through epistemological reasoning, whereas in the actual experience they are most often perceived as enmeshed, entangled. Time and space, as many anthropologists emphasise, are dimensions separated only by epistemological understandings.

In seeking an answer to the core question of our Walking seminar, I find it most meaningful to remain in-between, or, put differently, to “sit on the fence”. It is best to settle somewhere in-between—not on one side or the other, nor on the boundary or the division, but rather to dwell in the entanglements of all these diverse realms—whether visible, invisible, sunken, or shallow. It is best to sit on the Mozar (the 402 m hill in the northeast of the village of Črni Kal, known for its archaeological remains dating back to the Middle Palaeolithic that had an important role in the Roman period), where traces of the Palaeolithic and ancient Roman trade routes rest in the earth’s sediments, or at the hill above the Mozar, which once served as a strategic military position and today offers a view of terrestrial and aerial routes.

Let me return to the pathways and journeys, which are always in the making through numerous entanglements that shape space and time. The hike along the Karst edge undoubtedly led us through various edges, margins, depressions, and protrusions of time, which can be anything from deep to shallow, from the present, past, or future. In the journ-al-eying, I note a comment made by one of our colleagues in the Walking Seminar, as we ascended the hill and observed the Karst landscape and its countless edges: “The Karst Edge is eventually like the Slovenian Wild West.” The wilderness and its feral nature are undoubtedly hidden in the very name of the ridge, for which this part of the landscape is known as the Karst ridge. The Karst edge, or the so-called wild edge, is a point of numerous divides that does not allow the hiker to pause and sit on its edge, but rather to enjoy and travel in the wide view offered from the very edge. The Karst edge is also known as the area where different borders (i.e. the political border between Slovenia and Italy) and boundaries (i.e. the geological and climatic boundary between karst and flysch) and edges intertwine and generate numerous margins. The latter continuously shift and slip from their very meaning or lose their definitions. It seems that the Karst edge continuously seeks to form a single texture of space-time, where all distinctions and differentiations (e.g. between sunken and shallow, visible and invisible, movement and stasis, flysch and karst, Slovenia and Italy) meet and form a single unit. All is one, to echo Plotinus, or everything is unity and sameness.

This journeying could also be called journaling, as the written word often led my way of walking and thinking. My aim was not to form a clear argument or definition but to slip away from it. Walking, like thinking—thinking like walking? Walking and thinking are not merely physical or mental movements along, across, or through specific paths and landscapes (either physical or mental), but a way of dwelling that often, if one allows for it, reveals itself in particular time-scapes. The experience of walking and journeying is not shaped only by the material traces of landscape and pathways. Rather than accepting clear and defined meanings, or ways of knowing, sensing, and dwelling, it is perhaps more conducive — and adventurous– to allow for the complexity of time-scapes as textures, which continually open up the pathways towards both physical and metaphysical journeys.

Published October 2025. 2025/22